My father was a skilled and productive writer. He published many novels, including the recently reissued National Book Award nominee The Balloonist. There were a few non-fiction books as well: some early scholarly work about Italian literature, a book about solo sailing around the world, and a series of literature study guides for students with the usual plot summaries, discussion of themes etc. The crib books were the least important thing he had done, and my mother had done a lot of the work with him grinding out summaries.

Now, a leap. In the early 1990s I was an America Online user and an avid player of online trivia. Online social networks were very new, and this was a great one. Intelligent, educated obsessives battled for free online hours at a time when connection time was expensive. I made some good friends among the “Triviots” and not too many enemies, and some of these people are close friends to this day.

One day in chat I talked about my father and his work. Later I received an email from a fellow Triviot: Are you really this guy’s son? He changed my entire life around! We have to talk.

The email was from Fred Schreiber, an antiquarian bookseller in New York and a former professor of Classics.

And now, a lesson. The three paragraphs below are completely incorrect, which is why they’re in strikeout. I am not sure how this happened, but a story appeared in my mind — backed up by memories of conversations that did not occur — that is in fact not true. The story is told in the link below, and is very different: a working-class kid and compulsive reader, a love for books, and a formal education that started a mile behind and finished to win.

My Life With Books: How One Thing Leads to Another

After gently correcting my bizarrely fictional account, he was kind enough to say:

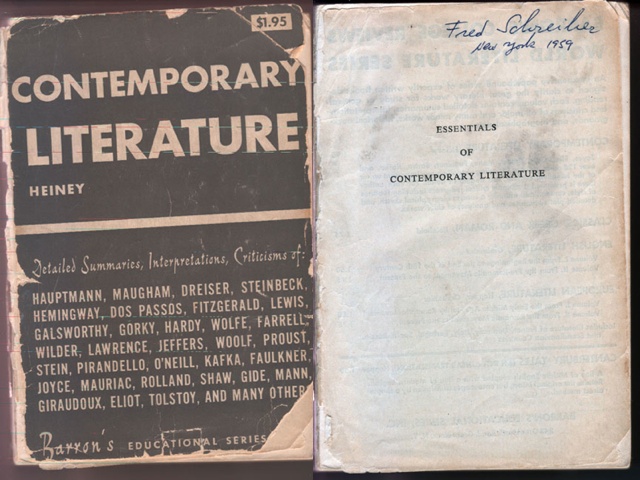

“The fact remains that your father’s book played a VERY BIG part in my early education; the proof is that I have kept it for well over a half century.”

So there we are, with a new story. At this point I really have no idea what part my father’s little book had, and I’m going to back slowly away from the story and just say that Fred’s pretty amazing. For my own part, I seem to have fallen into one of my father’s novels, possibly Hemingway’s Suitcase, in which the line between fact and literature becomes thicker and thicker as imagination and fraud switch places.

I apologize to Fred for inadvertently romanticizing him into a kind of high culture Horatio Alger character. The true story is better and more complicated than accidental fiction, as lives usually are.

Fred’s story did not begin in academia. In 1956, he was uninterested in school or anything else in the straight world. By his account, he was a tough guy headed for a working class life at best, and constantly in some kind of trouble. Some twist of fate, probably a court order, put him in night high school at the age of 21, taking bonehead classes and hating it.

For his sweathog English class, Fred picked up a copy of Contemporary Literature, one of my father’s crib books, with plot summaries and critical paragraphs to get him through this nightmare with the minimum of actual reading. And then something odd happened.

He became fascinated with the stories, the ideas, and the writers. In a recent email to me, he put it this way: “I remember how fascinating and instructive I found the book: your father had a way of telling the essential facts about an author in a most readable and elegant way.” I have to drag out a cliché here: a door opened for him into an entirely new world, full of stories and characters and ideas, the last thing he’d expected from an enforced trip back to high school.

The transformation took Fred from the streets of New York to college, graduate school, a Ph.D. in Classical Philology from Harvard, and a professorship at CUNY in Classics. He was as immersed in literature and ideas as a person could be, and loving it. When he got tenure and a job for life, though, he was immediately bored. He left academia and began dealing in old books. To this day he and his partner wife are E.K. Schreiber, dealer in books before 1700.

So this is the story of how a young person headed for a tough life in a hard city became a seller of “Early Printed Books, Incunabula, Renaissance Humanism, Early and Important Editions of the Greek & Latin Classics, Early Illustrated Books, Emblem Books, Theology, Early Bibles (in Greek & Latin).” And my father’s books were the key to that world. Not any of the award-winning novels, or the studies of Italian post-war literature, but the plot summary study aids he bought for $1.95 so he wouldn’t have to read his assigned work in remedial adult high school.

Publish! Record! Blog, even! Don’t just create, distribute, as far and wide as you can. To this day my father’s mostly out-of-print books are in libraries and used bookstores all over the world, in many languages. I have no idea if there’s just one Fred story there, or a thousand. If you have something to say or make, please put some effort into sharing it.

A bit of yourself, thrown far enough, hits the ocean and makes a little wave. You may never see the shore on the other end, never see the size as it breaks, but make the wave anyway.

Honestly, this was very inspiring. You just never know who will stumble upon your work and be changed for the better because of it.

Thank you for sharing this. Seriously fantastic.

LikeLike

That is a legitimately inspiring tale. And your point at the end is a good one (also a specifically useful thing for me to be reminded of right now, in regard to some photo stuff I’ve been attempting to attempt.) Keep writing, you.

I read another one of your dad’s books, Screenplay, quite recently. They had it on the shelf at the little old SLO library.

LikeLike